Cyber scams are no longer carried out by lone amateur criminals, but by real organized operations spread internationally. In countries like India, Nigeria, Ghana, and Pakistan, these centers operate with efficiency comparable to small or medium-sized businesses. They have a clearly defined hierarchy, assigned roles, dedicated tools, and a technological structure often more sophisticated than one might imagine. In today’s article, we dive into the so-called "Scam Cities" of Southeast Asia—one of the most prolific regions in the world when it comes to cyber scams.

The Criminal Organization

Within these centers, roles are assigned with clarity and specialization. We can identify:

- Dialer: Operators responsible for contacting potential victims through phone calls, automated email campaigns, or SMS messages. They represent the first point of contact with the target.

- Handler: Once a likely victim is identified, the case is escalated to more experienced personnel. These operators guide the victim through social engineering techniques until they gain remote control of the device.

- Closer: Handles the monetization phase. Their job is to transfer—or convince the victim to transfer—money, usually through hard-to-trace methods such as gift cards, cryptocurrencies, or mule account transfers.

- Manager/Supervisors: Oversee the entire operation, assign shifts, monitor operator performance, and manage the internal infrastructure, including security measures to prevent detection or information leaks.

This hierarchical structure allows these centers to operate with efficiency and scalability, much like a well-oiled corporate call center.

Tools Used

From a technological standpoint, these phishing factories are equipped with computer workstations using VPNs, proxies, VoIP systems, and remote access tools like AnyDesk and TeamViewer. It’s not uncommon for them to use VoIP switchboards based on Asterisk or FreePBX to mask the origin of calls.

In terms of infrastructure, these centers utilize SMTP servers (often compromised or rented from offshore providers) to launch massive phishing campaigns. Emails are often crafted using prebuilt phishing kits, purchased on specialized forums or Telegram channels, that closely clone the appearance of online banking, email portals, or cloud services. Phone spoofing techniques are also commonly used to fake the caller IDs of banks or public agencies.

Attack Techniques

Another increasingly common technique is domain shadowing, which involves abusing legitimate (often compromised) subdomains to host phishing pages. Technical infrastructures often rely on cheap VPS servers in uncooperative jurisdictions, and many operators use IaaS (Infrastructure-as-a-Service) to quickly scale their operations.

The attack methods are no longer limited to email phishing. Deceptive SMS messages (smishing) and automated phone calls (vishing) with pre-recorded messages are now routine in these centers. In the mobile ecosystem, the use of trojanized Android APKs is becoming more common—apps that appear harmless but, once installed, steal credentials and intercept OTPs.

Social engineering remains the core of their attack model. Scammers follow detailed scripts, study victim behavior, and adapt to their responses. Information gathered from data breaches or OSINT (social media, forums, old emails) is used to make interactions even more convincing.

Once credentials or financial data are acquired, the monetization phase begins. Gift cards are frequently used—converted into goods, resold, or exchanged in underground markets. Cryptocurrencies are the ideal tool for anonymously laundering and cashing out funds, often using mixers or privacy-oriented wallets like Monero. The most organized fraudsters use mule accounts—bank accounts held in the names of unsuspecting individuals—for transfers that appear legitimate.

To avoid detection by security systems, these centers adopt increasingly advanced tactics: rotating IPs and domains, using polymorphic crypters that change a malware’s hash with each execution, and monitoring blacklists and threat intelligence platforms to prevent their domains from being flagged. Others use time-based attacks, where phishing pages are active for only a few hours—just long enough to hit a specific target before disappearing.

The Scam Mechanism

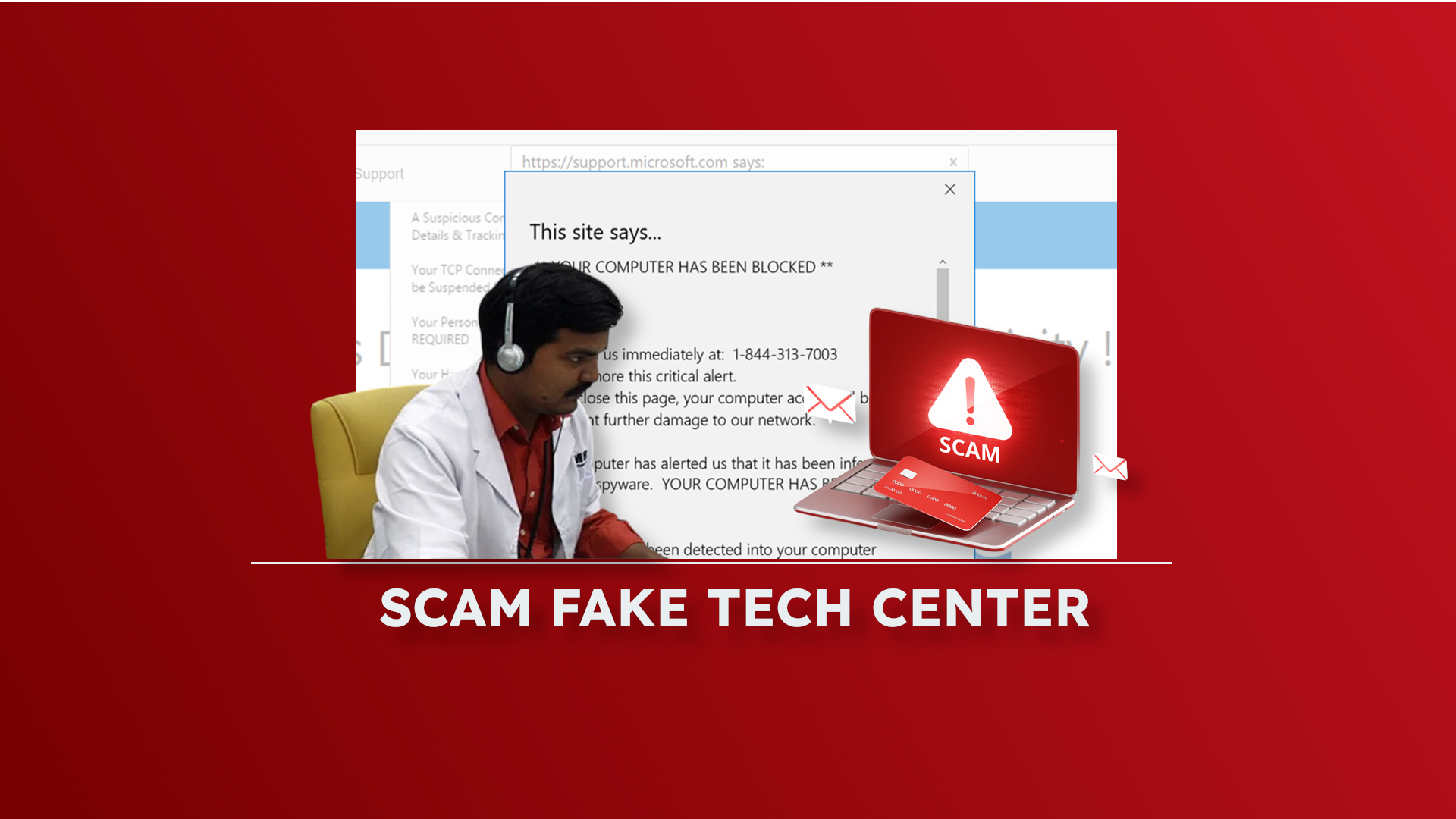

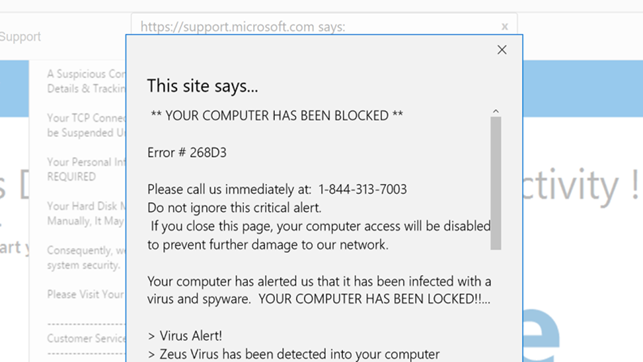

Most attacks begin with fraudulent advertising mechanisms: banners or pop-ups that simulate critical OS errors and prompt the user to call a support number.

Once contact is made, the scammer convinces the victim to allow remote access via tools like TeamViewer, displays fake system logs, runs harmless terminal commands to simulate antivirus scans, and persuades the victim to pay for an "urgent repair."

In many cases, interactions with victims can last over an hour.

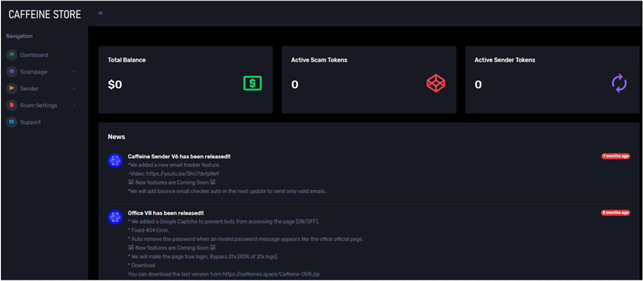

This approach shows that phishing is no longer just about clicking a malicious link, but a well-orchestrated social engineering operation, persistent and technically designed to bypass both technological and psychological defenses. It is truly criminal enterprise, supported by Phishing-as-a-Service platforms that allow anyone to purchase full kits, servers, manuals, and even tech support. Some centers have introduced internal dashboards to track KPIs such as clicks, conversions, and earnings, along with affiliate programs that reward those who bring in new victims. This level of operational efficiency makes these services a serious threat to global cybersecurity.

How to Defend Against It

Defending against these attacks, by their very nature, cannot rely solely on having a good antivirus—though it remains absolutely necessary. What’s essential is widespread and up-to-date security awareness: understanding the threats surrounding us in the digital world so we can recognize and avoid them.

Bonus tip for businesses: It’s highly recommended to correctly configure SPF/DKIM/DMARC records, implement systems for automatic detection and reporting of suspicious emails, and use threat intelligence feeds to track IPs, domains, and TTPs (tactics, techniques, procedures) of active groups.

Conclusion

Scam and phishing centers are no longer just a curiosity covered in occasional news reports.

They are fully-fledged cybercrime enterprises. Understanding how they operate, the techniques they use, and the evolution of the infrastructures supporting them is essential—for law enforcement agencies working to dismantle them, for cybersecurity experts protecting businesses, and for everyday internet users seeking to protect themselves.